Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

Let’s state the obvious: In recent decades, a college degree has become increasingly important and increasingly out of reach for the poor, middle and working classes.

Since 1978, a four-year college or university has become 1,122 percent more expensive to attend. Americans held $1.3 trillion in student loan debt in 2015 — more than credit card debt.

At the same time, the value of a college degree is at an all-time high, according to a Federal Reserve study. Over the course of a lifetime, a college graduate typically makes $570,000 more than a high school graduate. Brookings researchers Michael Greenstone and Adam Looney found a college degree is the best big investment a young person can make.

[Read more: UMD doesn’t have to pay P.G. County’s minimum wage. These groups want to change that.]

The problem is fairly simple: A college education is both unaffordable and critical to one’s success in life. The best solution to this problem is equally simple: Make public college free. Essentials are, well, essential. Success in the market shouldn’t determine access to essential goods. That’s why the government, very broadly speaking, uses tax dollars to guarantee citizens functioning roads, police protection and primary education.

To be sure, the state often fails to secure these public goods, and plenty of essentials — food, medical care, etc. — have yet to be decommodified. That doesn’t deter from the basic and powerful principle that one should have access to necessities, whether or not one is good at accumulating cash. And, at this moment, in this economy, a college education is becoming a necessity.

Some progressives might claim that it’s silly to make public college free for everyone. Why should Donald Trump’s children have access to free college? My answer is practical: Programs for all have more staying power than programs for a few. Universal public programs — say, social security or public primary education — are easier to protect than means-tested programs — say, Medicaid — which serve less powerful constituencies and are, therefore, vulnerable to cuts.

But a federal program to decommodify higher education is quite unlikely under this president and Congress. Until our representatives in Washington, D.C., are more open to the idea of free public college, students should concentrate their anger and activism on unionizing undergraduate workers.

[Read more: UMD student coalition teams up with Maryland delegate to push collective bargaining rights]

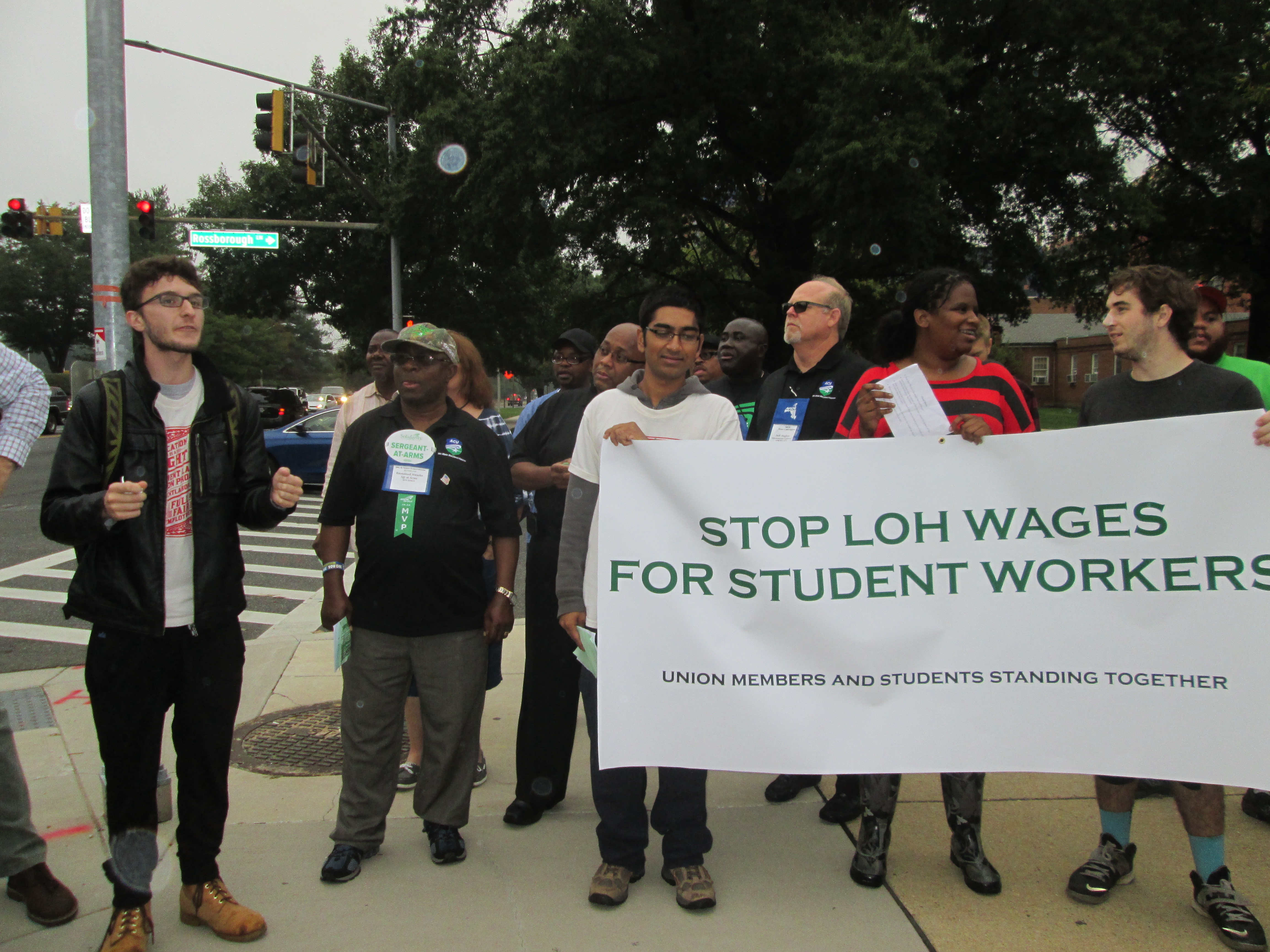

For most undergraduates, work is a part of the college experience — four out of five college students work part-time, for an average 19 hours a week. Facing spiking tuition bills, many undergraduates must work to limit future debt. And yet, students often lack the protections and dignity they deserve. For example, undergraduates at the University of Maryland don’t have collective bargaining rights, and the university doesn’t have to pay them Prince George’s County minimum wage.

Collective bargaining rights and undergraduate unionization are worthy causes for obvious reasons: Workers get higher pay, stronger protections and a greater say in the workplace. Student dining workers at the University of California, Berkeley organized the Undergraduate Workers Union, occupied a cafe on campus and extracted longer breaks and back pay. At Grinnell College, a union of student dining workers signed a contract with management that raised hourly wages by nearly a dollar and set up a workplace grievance process.

The union struggle perfectly prepares students for the free college fight. Both policy advocacy and worker solidarity require organizing. And the fight for undergraduate labor rights builds student power. It shows the powers that be — from employers at this university to university President Wallace Loh to the U.S. Congress — that they must take undergrads seriously.

Student workers who care about labor rights should check out this university’s chapter of the Student Labor Action Project, which does fine work. In recent years, representatives in Annapolis have introduced legislation to give undergraduates collective bargaining rights. The only way students can win that fight is to organize and build political power. And that political power will be critical in the biggest student fight of all: Making free college education a right.

Max Foley-Keene, opinion editor, is a sophomore government and politics major. He can be reached at opinionumdbk@gmail.com.