On Sunday night, Stephen Paddock opened fire on an enormous crowd of festivalgoers from the 32nd floor of Las Vegas’ Mandalay Bay Resort. He killed 59 people and injured about 500 others in the deadliest mass shooting in modern American history.

As immense and tragic as the incident was, it’s not unique. Mass shootings plague headlines and 24-hour news cycles, and it seems that with each new one we can expect a new fatality record with it.

The thing is, gun violence has become almost commonplace, desensitizing us to the point where we’re no longer surprised. The response is the same each time, too: Politicians urge for more gun restrictions or attribute it to extremism, the masses collect on social media to voice their opinions and nothing ever gets done. Mass shootings occur once more. The cycle repeats.

Tighter gun restrictions are critical to prevent handguns and assault rifles from getting into the hands of those who commit mass shootings, but it’s not that simple. What we’re missing from this discussion is the history of gun control interlaced with its sinister prejudice and racism.

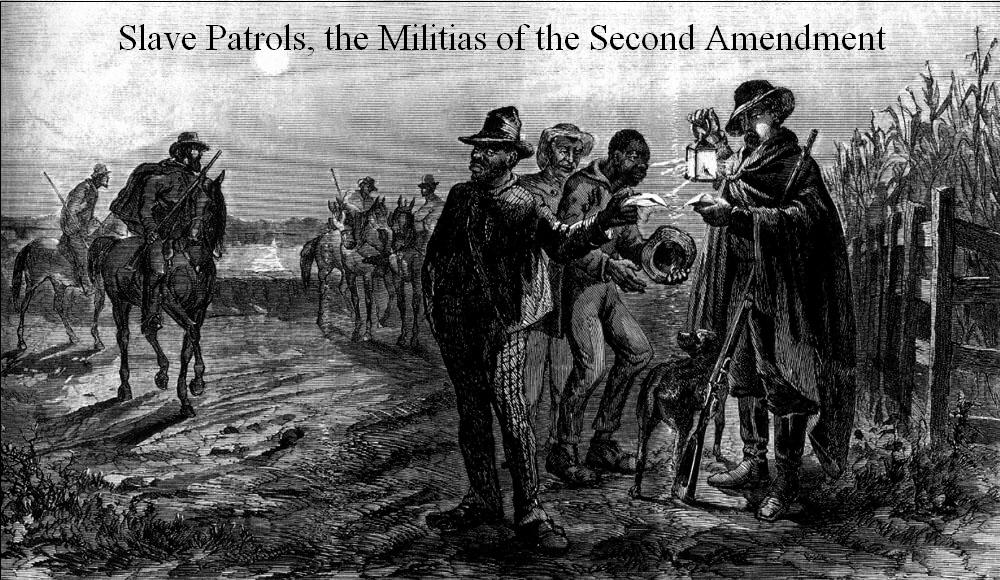

Gun ownership policy has possessed racist undertones well before the Second Amendment proclaimed Americans have the “right to bear arms.”

In the mid-1750s, Louisiana colonists were legally allowed to beat “any black carrying any potential weapon, such as a cane,” if they deemed it necessary. What if they resisted? Well, then the colonist had every right to “shoot to kill.”

During those colonial days, restrictions on blacks carrying weapons reached an extreme because of the states’ “dread fear of armed blacks,” according to historian Clayton Cramer. In Maryland, free black people couldn’t even own a dog without obtaining a license first, because lawmakers worried a dog could be used as a weapon.

Fear of armed black men escalated, prompting states to revise their constitutions and clarify black men did not have the same rights as white men. The Tennessee Constitution changed a mandate on the right to bear arms to say it applied to “free white men” instead of “freemen.”

Times have obviously changed; rights have been increasingly granted to people of color, and there is no longer a state law that overtly prohibits black people from owning guns. But it does not dismiss the reality that subtle, institutionalized racism — which does exist today — paints black people who do own guns in a malicious light.

Black people continue to suffer the most due to gun violence. Nationally, they are twice as likely as white people to die by gun. In Washington, D.C., this increases to 13-and-a-half times more.

The fear of armed black men is still alive and well, as seen by the many officer-related gun incidents in the last couple of years. A haunting reflection of white citizens’ decades-old fear manifests in the modern belief that if there’s even a slight possibility a black man may have a gun on their person, they can be justifiably shot.

Philando Castile was shot by a police officer who thought he was reaching for a gun. Tamir Rice was a 12-year-old boy with a pellet gun shot within two seconds of an officer pulling up next to him.

Before we jump into the oversimplified solution of increased gun control, it’s critical to explore the paradoxical experiences of black people owning guns. Tightening gun control is racially charged because it’s targeted at limiting targeted groups’ power, while the lack thereof creates a world where innocent black men die under the pretense of gun ownership. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution, and policymakers must work to fix the racial double standard about gun ownership before the cycle begins again.