Alternating from topics of sappy love to melancholic meditations on race, gender and identity, Instagram has created the snapshot poem — a brief piece that can fit in the size of an Instagram photo, easy to read while scrolling.

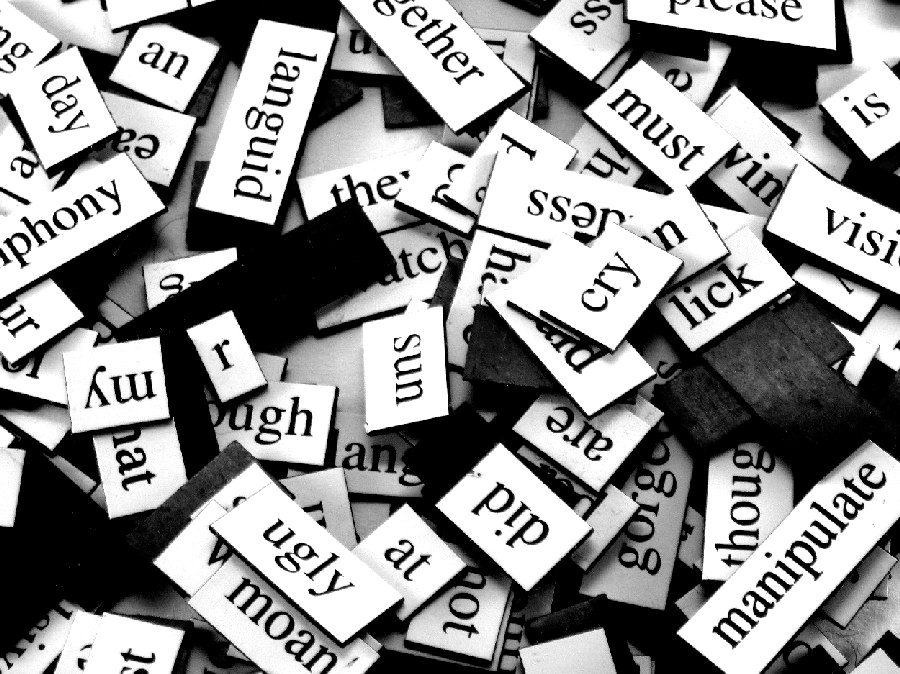

Part of the beauty in writing poetry restrained to a certain form is that it forces the writer to think in new ways. Instagram poetry is the opposite of poets like Tennyson and Milton, and the only restraints are that the poet fits their words in a square.

In a way, this acts as permission to make poems short. In the past, this restraint came from syllables: a haiku, for example. With Instagram, it is physical space that poses limitations for the poet rather than syllables, rhyme or meter.

This has positive and negative effects. In reality, it’s a free-for-all where any thought can be indented and put up in typewriter font and voila! It’s a poem. However, in this mess there are still some poets who rise to the surface.

Nayyirah Waheed and Yrsa Daley-Ward are two such poets.

To her 174,000 followers on Instagram Waheed promotes body positivity, self-love and conversations about race and culture through brief poems. Her books, “salt” and “nejma” are available on Amazon for an international audience. Daley-Ward focuses on race, sexism, family and more in her book “bone.”

Other accounts such as atticuspoetry with 268,000 followers, Christopher Poindexter with 295,000 and Tyler Knott Gregson with 302,000 add their voices to the online conversation. Gregson also has books available on Amazon.

The question is whether Instagram itself generates this poetry or if poets who already write short poems have found a perfect medium. The answer is likely a mix of both, but the format of Instagram poems allows for a wider audience as opposed to a blog or a website because people are constantly scrolling and digest a wider and briefer range of material.

Plus, Instagram is arguably more visually appealing and easily approachable. It provides idea snapshots, or poem selfies, whichever sounds best.

In all, Instagram is a new avenue for even the shiest poets to post their work. They publish with the click of a button. They don’t have to send any work out to editors or endure a grueling publishing process. They can also filter who reads their poems, if they desire, by making an account private and only accepting followers they’re OK with.

Among other online platforms, Instagram has altered what it means to be a poet and enhanced a new form of short poetry altogether.