Crimes and misdemeanors

FACEOFF by Dean Essner and Michael Errigo

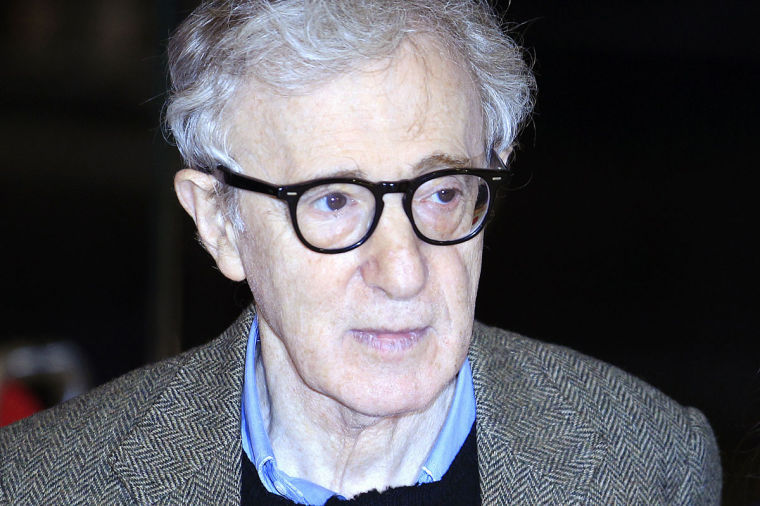

NO: Allen’s persona and art are inseparable

As a self-deprecating Jewish man with a tendency to overshare and use his friends as therapists, I’ve never found it hard to identify with many of Woody Allen’s films.

More specifically, I’ve found similarities with Allen himself — or at least the persona he returns to again and again in his films. We’re both obsessed with death. We both turn pale when thrust into a room with too many people. We both love New York even though its residents frustrate us.

With that in mind, the molestation allegations made against Allen by Dylan Farrow — Allen’s adopted daughter from his relationship with actress Mia Farrow — are disconcerting on multiple levels. In one regard, I feel even more uncomfortable with the real-world Allen. That’s a given. Even if he didn’t commit this heinous sex crime, he’s still had a questionable romantic life: various broken, short-lived relationships and, of course, his current marriage to Soon-Yi Previn — another one of Mia Farrow’s adopted daughters.

At the same time, though, I don’t think I can identify with Allen’s on-screen persona any longer. There comes a point at which the sordid circumstances of an artist’s life completely sully the art they’ve made. And I think — though it pains me to admit this — I’ve reached that point with Allen. I’ll never be able to watch his films the same way because the allegations loom large in every frame.

Even worse: It’s difficult not to think back to his movies and piece together the seedy fragments of his ulterior temperament. For instance, misogyny is a prevalent theme in many of his most iconic films, even if we try to pass it off as a byproduct of endearing romance.

Annie Hall is essentially about a man and his attempt to help his naive girlfriend become as worldly and thoughtful as him. Manhattan features an ill-advised relationship between Allen and a teenage girl, whom he also wants to educate and shape into an adult. One of Crimes and Misdemeanors’ central plots involves a clingy mistress who is murdered because she won’t reveal the affair she is having with a married man.

Women exist in Allen’s movie universe as little more than blank canvases, objects for sculpting that arrive callow and leave full of wisdom and intellect. Even if they get away because they eventually outgrow the male protagonists, we do not forget who taught whom.

After her relationship with Alvy Singer (played by Allen), Annie Hall learns to love poetry and finds enough confidence to pursue a music career in Los Angeles. She even chooses to go see The Sorrow and the Pity — Singer’s favorite film and a key example of his obsessive intellectual suffering — at her own will. He takes her to see it early on in their relationship, and by the end of the film, his suffering becomes hers.

And now his suffering has become mine.

—Dean Essner

YES: The movie and the man are not the same

If Woody Allen is a child rapist, is Crimes and Misdemeanors still thought-provoking? Is Midnight in Paris still imaginative? Is Match Point still thrilling? Is Annie Hall still legendary?

Allen has been in the spotlight since allegations that he molested the underage daughter of then-partner Mia Farrow in 1992 have thrust their way back into the public consciousness. First, there were tweets from Farrow and her son Ronan that — directly and indirectly — criticized the Golden Globes for awarding Allen a lifetime achievement award. Next came the open letter sent from the accuser, Dylan Farrow, to Allen via The New York Times. Allen responded in turn by continuing to deny any wrongdoing.

All of these events have made the past the present once again as the media obsess over every detail, accusation and counteraccusation. Those seeking wood to fuel the fire have turned to his most recent film, Blue Jasmine, claiming the unstable protagonist, played by Cate Blanchett, is a veiled shot at Mia Farrow.

Whether any of these allegations are true remains to be seen. However, they should not in any way impact the legacy of his movies. A good film is a good film, regardless of the names attached to it — and there is no shortage of good Woody Allen films. It’s unnecessary to psychoanalyze each character, searching for evidence of reality bleeding into fiction. It’s possible to view them as nothing more than good films with entertaining storylines and well-drawn characters.

To decry Allen and his movies would be inconsistent with the public’s tendency to forgive and forget the sins of stars. Once the media firestorm subsides, people tend to move on. Perhaps this points to a problem with the low expectations we have for our celebrities, but given that Allen has never been convicted of anything, it would be overzealous to condemn the man’s filmography. The artist can be separated from the craft.

Even if you link the movie with the man, consider this: Reports of the alleged misconduct surfaced in 1992. Since then, Allen has made 21 movies that have earned more than $250 million combined. He has worked with a laundry list of Hollywood elite, including Leonardo DiCaprio, Robin Williams and Sean Penn. In 2007, the American Film Institute named Annie Hall the 35th-greatest movie ever made. His films have been nominated for 19 Oscars and have won three, and many predict Blue Jasmine will earn Cate Blanchett a golden statue come March. He is beloved.

Obviously no one cared before, so why start now?

—Michael Errigo