Senior J.T. Stanley is tired of hearing that University of Maryland officials have plans to address sexual violence on the campus — the time for that was yesterday, he said. Or last semester. Or even four years ago.

In late April, this university was three votes short of approving an amendment in the Sexual Misconduct policy that would have created a comprehensive, strategic plan for sexual misconduct prevention as well as mandated in-person sexual violence and rape culture trainings for students. The amendment, which failed to pass with a 35-32 vote, called for mandatory sexual violence and rape culture training and education in freshman orientation, during move-in weekend and for UNIV100: The Student in the University and the equivalents.

“That would have been the biggest prevention reform, as far as I know, in our school’s history,” said Stanley, an individual studies major and senator representing the Behavioral and Social Sciences College. “It’s a big deal it lost by three votes.”

This university currently requires an online sexual misconduct training; there will also be a session about campus safety with attention to sexual assault during freshman orientation this summer, and Step Up bystander training will be added into UNIV100 courses and the equivalents in the fall. However, there is nothing in university policy or procedures that requires any sexual violence or misconduct prevention.

This university is mandated by the Campus Sexual Violence Elimination Act to provide education on primary prevention and awareness for incoming students and employees, said Title IX Coordinator Catherine Carroll. This is done through programming and speakers, she said, but she hopes to do more through a “robust and comprehensive” prevention plan.

Stanley said he agrees.

The online misconduct training, orientation and UNIV100 initiatives, he said, don’t get at the core issues behind sexual violence and tend to focus on sexual misconduct from a reactionary angle. The only education he thinks addresses this is the sexual violence presentation run by the CARE to Stop Violence office, which isn’t mandated for students.

“It’s something, but it’s nowhere close to where we need to be,” Stanley said. “[The online training] is an important training, but we still need in-person sexual violence training.”

FALLING SHORT ON THE SENATE FLOOR

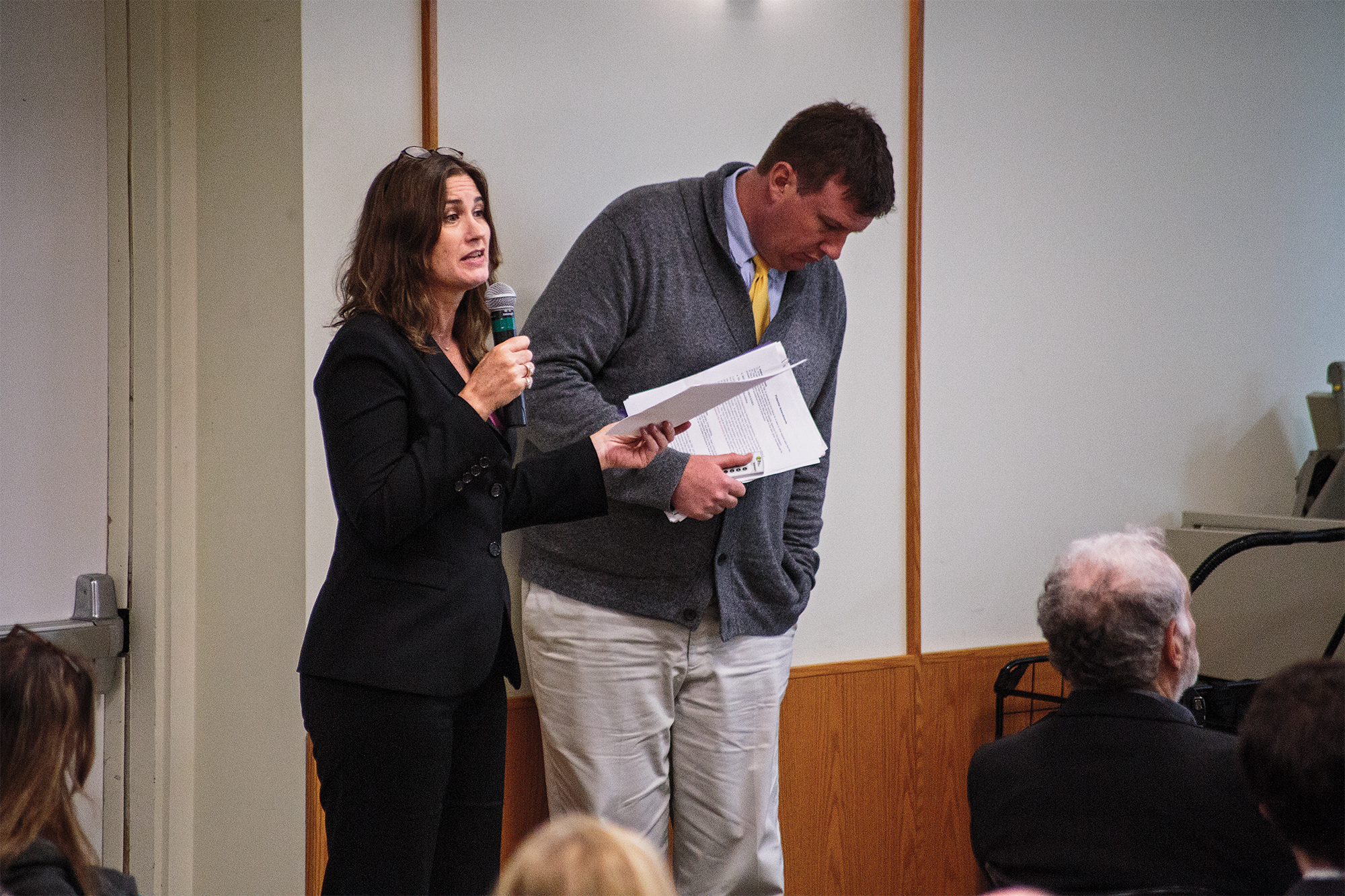

Stanley and fellow undergraduate senator Lydia Yale introduced the Sexual Misconduct policy amendment at the April 28 meeting to highlight the issue of sexual assault and violence. The state had mandated that the senate vote on an updated Sexual Misconduct policy, which Yale said made that meeting an “opportune moment” to bring up their ideas.

“In conversations with people, we’ve talked about it as an epidemic,” said Yale, an architecture major and a representative for the Architecture School. “It just has such a strong effect on people and it’s not being paid attention to.”

Students who spoke at the meeting showed their support for the amendment, while employees focused more on the specific issues of the language, placement and timing. There was consensus, however, that the idea was worthy.

Carroll cautioned, however, that the amendment should not be in a policy document because it specified procedures and was premature without having longer discussions from all the stakeholders involved — including students, she said.

“We are really trying to do a lot on this campus,” Carroll said. “We are in the planning stages of creating a stakeholder group across campus to develop a comprehensive strategic plan, so we’d do prevention in a meaningful, measurable way.”

Senate Chair Jordan Goodman said he agreed with Carroll that the idea was too last-minute, noting that, “It’s hard in the senate to bring up a substantive amendment that hasn’t been vetted.”

But for student leaders at the meeting, there is no more time to wait.

“The support for an amendment like this from undergraduates is overwhelming,” said Kevin Bock, an undergraduate Computer, Mathematical and Natural Sciences senator who attended the meeting. “I think while the current framework may not be exactly that case, I feel like it’s important to change the stance of the document from purely reactionary to proactive.”

Stanley and Yale also introduced an amendment on April 28 that would have required semester reports from the Civil Rights and Sexual Misconduct office — something the office currently does annually — with numbers about how long investigations, adjudications and sanctioning last for any case that goes through the office. This amendment was short five votes.

“To reinforce the transparency and accountability of this policy would be huge for not only me but a huge percentage of this university,” said Yale, who reported her sexual assault case in December and said she received their determination within the last three weeks.

Carroll said she cannot comment on specific investigations. However, she said her office is under-resourced, which is making their work move slower.

When dealing with sexual misconduct cases, the university “strives to take appropriate action … within sixty (60) business days,” and requires that students receive notice of any delays, according to this university’s sexual misconduct policy. However, Yale said she rarely received notifications during many months of waiting.

“I haven’t gotten very much notice throughout unless I initiate the contact,” Yale said.

Yale hoped more reporting would show how these complaints are dragging on, which is likely because there is a lack of resources and large demand, she said. In the 2014-15 school year, there were 112 reports of sexual misconduct. Out of those 112 reports, there were 48 complaints filed and 64 incidents reported, according to the Civil Rights and Sexual Misconduct office.

“When the investigation is going on, there’s always something in the back of your head where you’re thinking about it,” Yale said. “It’s your life. … These people are handling how your trauma is going to be resolved and they’re not telling you anything.”

Carroll said she is in favor of transparency but is worried her office doesn’t have the capacity to expand their reports.

“That’s good information to ask, [but] we don’t have adequate infrastructure in place to easily produce that information,” Carroll said. “We’re a new office on campus, we barely have infrastructure, we’re understaffed, we don’t have a data management system … It’s important that people understand that we’re doing the best we can.”

MOVING FORWARD

Stanley said he has no plans to stop fighting for better sexual violence prevention on the campus.

In addition to advocating for the amendment to the Sexual Misconduct policy, Stanley and Yale teamed up this semester to write a proposal that would create a comprehensive, strategic plan for sexual misconduct prevention. While this university has policies and procedures for sexual misconduct when something goes wrong, Stanley said everyone will benefit more from a proactive prevention plan.

“One in five women [in the U.S.] will be raped at some point in their lives,” according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, and, “One in five women … are sexually assaulted in college,” according to the Justice Department’s National Institute of Justice.

“We’ve heard so much rhetoric about how people care, but we haven’t seen the actual commitment,” Stanley said. “There was no clear place where it was going to come from, and it was indefinite.”

Stanley and Yale did not introduce their proposal to the senate this semester because they didn’t get the explicit support from Carroll as they had hoped. But this fall, when Stanley returns for his final year, he said he will be submitting a proposal for such a prevention plan.

While she didn’t agree with the initial wording of the amendment or what she saw of their prevention proposal, Carroll noted she does support the idea of a campus-wide, comprehensive, strategic plan for prevention. It is on her agenda, she said, and she hopes to kickstart it this summer by bringing together different stakeholders on the issue, such as representatives from this university’s CARE to Stop Violence office, national philanthropy Men Can Stop Rape, as well as campus leaders, the Student Government Association, administration and students.

“What I want the plan for is to not just be strategic and meaningful about what we do when it comes to prevention, but more importantly I want to be able to measure over time if our prevention methods are making a difference,” Carroll said. “I don’t think it’s prudent for us to jump on the bandwagon of one or two individuals’ ideas and say that’s what we’re going to do for the university, because it’s a much bigger issue.”

After dealing with the busy office, Yale said she’s skeptical Carroll will be able to bring this idea to life.

“If she were to make that prevention group it would be so amazing and I would be very happy,” Yale said, “but from what I’ve seen, it doesn’t look very promising.”

Staff Sen. James Bond from the Office of Student Conduct said he is happy to hear Stanley is planning to continue his efforts.

“I hope they’re not discouraged at the outcome [of the votes at the April 28 senate meeting], because I don’t think that’s emblematic of the concern that the senate or campus puts on these issues,” Bond said.

Goodman agreed he was glad the students brought up the issue and added that he hopes it doesn’t stop there.

“If they bring something up, I think we would almost certainly assign that to a committee that will satisfy what they want to do,” Goodman said.