The more technology reaches into our everyday lives, the more we are fascinated by it.

But while paper mail is struggling, newspapers are dying and notebooks are being exchanged for computer screens, plain old hard-copy books aren’t disappearing as fast as everyone thought they would.

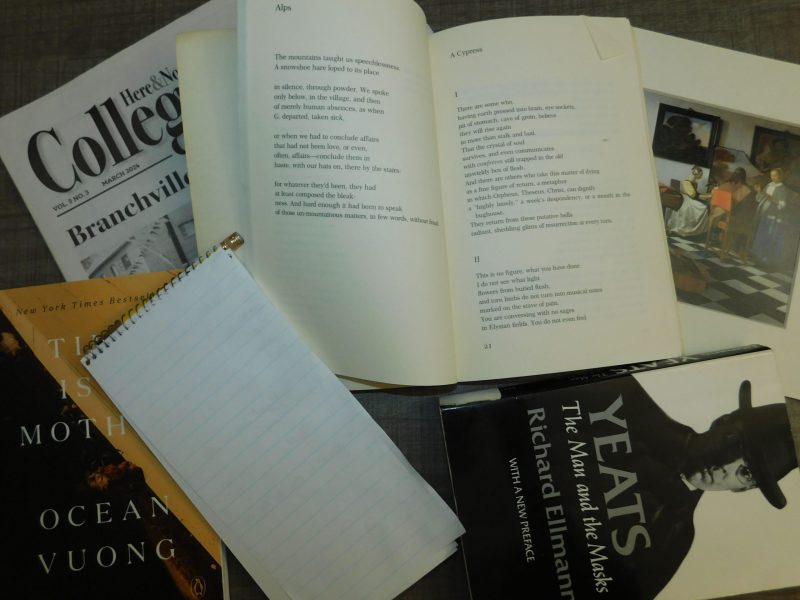

Perhaps that’s because bibliophiles love the smell of musty paper or the muted thud of victory when they close the back cover. Sure, e-books have been commonplace for a while now and Kindles and Nooks had their run as the Christmas present of the year, but a trip around McKeldin Library suggests even millennials, born in the digital age and raised on glowing LED screens, love a real solid book.

Computer science major Abrar Saleh reads exclusively hard copies, and so do all his friends.

“I like having the book there,” the freshman said. “The physical feel of it while you peruse the pages — you don’t get that kind of feeling when you’re reading something online.”

The truth is that e-books don’t add much new to the experience. Of course, they’re smaller and lighter, but there are plenty of hard copies that also fit that bill. And the convenience of downloading a new book? That’s only particularly useful if you plan to read more than one book at a time.

Sophomore accounting and economics major Debbie Shields echoed Saleh’s sentiment. She just doesn’t see much of a reason to switch.

“If there was a book that was only on e-book I would try it, but I prefer hard copy,” she said. “I think the physical feel of an original book is better than an e-book. I don’t find it inconvenient.”

Reading seems to be the one area where even young people are resisting change, but if students will pick a movie off Netflix instead of popping in a DVD, could the same work for books?

Two competitors — Scribd and Oyster — set out to try just that. Launched in 2013, Oyster offered subscribers access to an enormous reading library for less than 10 bucks a month. Scribd opened its virtual doors in 2007 and offers audio books, documents and sheet music as well. Subscribers can access three books and one audiobook a month, plus a variety of extra non-book features.

But after two years, Oyster announced last fall it couldn’t afford its customers’ reading habits and will cease to exist in 2016. Scribd has had to stop offering romance novels because it couldn’t afford to pay for as many as readers were eating up.

It might be hard to believe that Oyster, marketed as “Netflix for books,” is having a hard time keeping up. But maybe that’s because movies and shows were made for the screen. Before the technology to project them, they simply did not exist. Meanwhile, the book is being forced into a medium it thrived without since the Epic of Gilgamesh.

So why not make a book specifically for the digital age? By recruiting authors to write for a new way of reading, Atavist Books published an interactive novel that allowed readers to wander through virtual images and accompaniments and even pick a character and location they wanted to explore.

The idea didn’t stick, and after two years in business, Atavist closed down. Not only are hard-copy books hanging on, they’re soundly defeating companies backed by multimillion-dollar investments.

Maybe it’s because e-books, audiobooks and interactive books are all attempting to reinvent something that needs no reworking. For history major Andrew Parker, books are simple.

“If the power goes out, I can still read a book,” he said. “I can take a book on a trip and I don’t have to worry about the battery in my book.”

Despite fancy money-backed attempts to recreate the book, the senior doesn’t see McKeldin’s dusty shelves disappearing anytime soon.

“People are really into books,” he said. “There’s always going to be some part of the population that says, ‘No, we want physical books. That’s the way it used to be.'”