Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

During the announcement last week that Prince George’s County will sue opioid manufacturers for peddling addictive painkillers to county residents, Fire Chief Ben Barksdale noted that administrations of Narcan, a drug that reverses the effects of an opioid overdose, have increased 260 percent since 2014. During that same period, the price of Narcan has increased 50 percent.

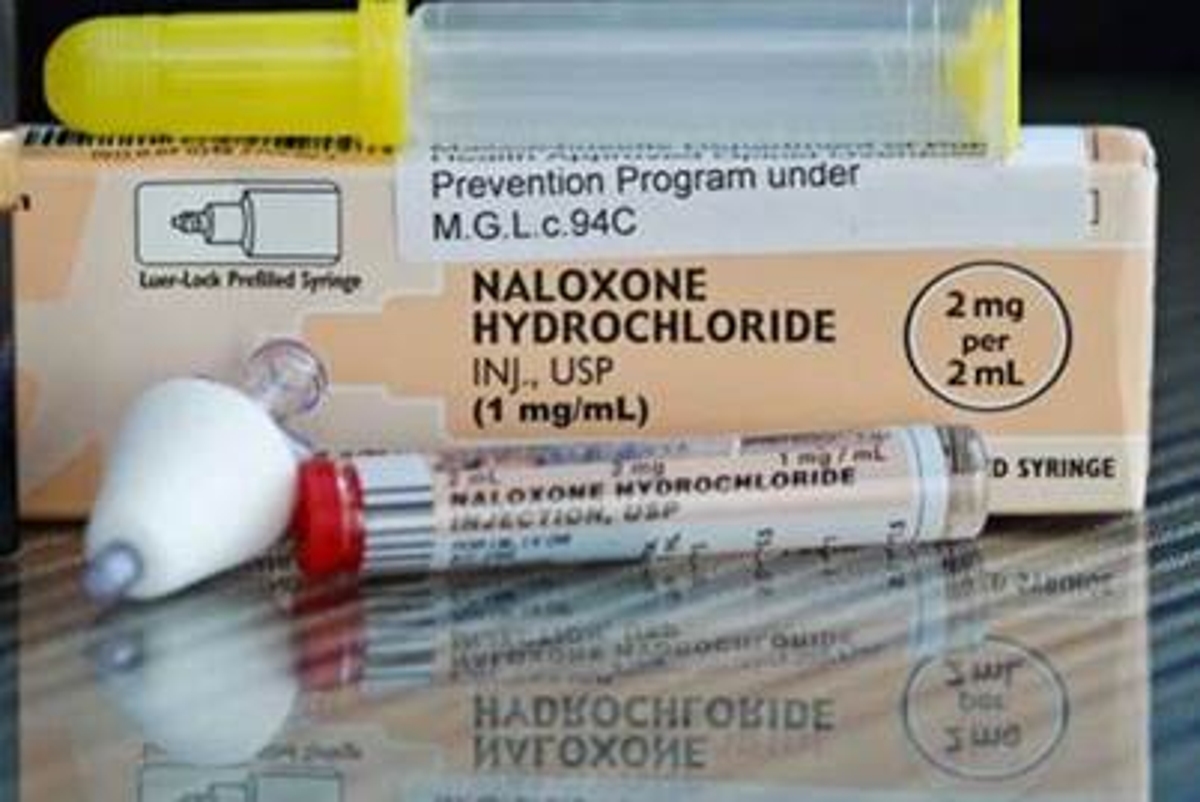

Price hikes pervade opioid treatment. Evzio is a popular injector device used to deliver Naloxone, the generic name for Narcan. As demand for Evzio grew, its manufacturers increased prices from $690 in 2014 to $4,500 in 2017, handicapping efforts to prevent overdoses.

[Read more: Prince George’s County is suing opioid manufacturers]

These price increases are massive obstacles to opioid treatment. The solution to this problem — and inflated medical prices in the U.S., in general — is to authorize the federal government to directly negotiate costs with pharmaceutical companies.

On one level, it’s intuitive that opioid treatments are becoming more expensive: As demand increases for a product, the manufacturer raises prices. But, of course, demand is spiking for Narcan and Evzio because America is in the midst of an opioid crisis that’s ending tens of thousands of lives each year. That crisis has caused the U.S. life expectancy to drop for the first time since the AIDS epidemic and, absent coordinated action, is expected to kill 650,000 Americans during the next decade. Pharmaceutical companies fuel a brutal cycle: As more Americans get addicted, overdose antidotes become increasingly necessary, causing price hikes that, in turn, make it harder to treat overdoses.

It’s revolting that firms can profit off restricting access to life-saving drugs. But it’s a mistake to reserve our moral opprobrium for specific individuals and companies. Warped incentives prevent the health outcomes citizens of the richest nation on earth should expect.

Economists have long known the real problem in American health care is extremely high prices. For example, an MRI in the United States costs $1,119 on average — in Australia, the procedure costs only $215. This problem is especially acute in drug markets. The U.S. leads the developed world in pharmaceutical spending; on a per capita basis, each American spends more than $1,000 on prescription drugs each year.

[Read more: Amid county lawsuit, report shows 18 percent hike in Prince George’s County opioid deaths]

The reason is simple: The U.S. government doesn’t negotiate prices with pharmaceutical companies. As Sarah Kliff ably describes for Vox, most developed nations have a government agency — in Australia, it’s the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee — that will evaluate whether a drug brings necessary value to the market and, if so, will recommend its price. Drug companies are willing to bargain down prices because these government entities can guarantee market access to an entire nation.

In the U.S., however, each insurance company individually negotiates prices with pharmaceuticals. And because we have many insurance companies here, each individual insurer has far less bargaining power over Big Pharma. Instead of offering access to a national market, American insurance companies can only offer access to their customers. Not even Medicare, America’s largest insurer, has the authority to directly negotiate drug prices. As Tom Sackville, who runs the International Federation of Health Plans, explains, “The system is so divided, it’s easy [for pharmaceutical companies] to conquer.”

Here’s what a more just system might look like: One government insurer — we could call it, say, “Medicare for All” — would be granted authority to negotiate with pharmaceuticals. This body could bargain down the price of drugs like Narcan and medical equipment like Evzio, easing the battle against opioid addiction and expanding access to all types of essential medications. Giving the feds power to drive down health care expenditures is a critical step in satisfying an abiding moral imperative: divorcing health care from private profit.

Max Foley-Keene, opinion editor, is a sophomore government and politics major. He can be reached at opinionumdbk@gmail.com.