Six University of Maryland scientists partnered with Duke University to build a protein-sugar that could potentially lead to an HIV vaccine.

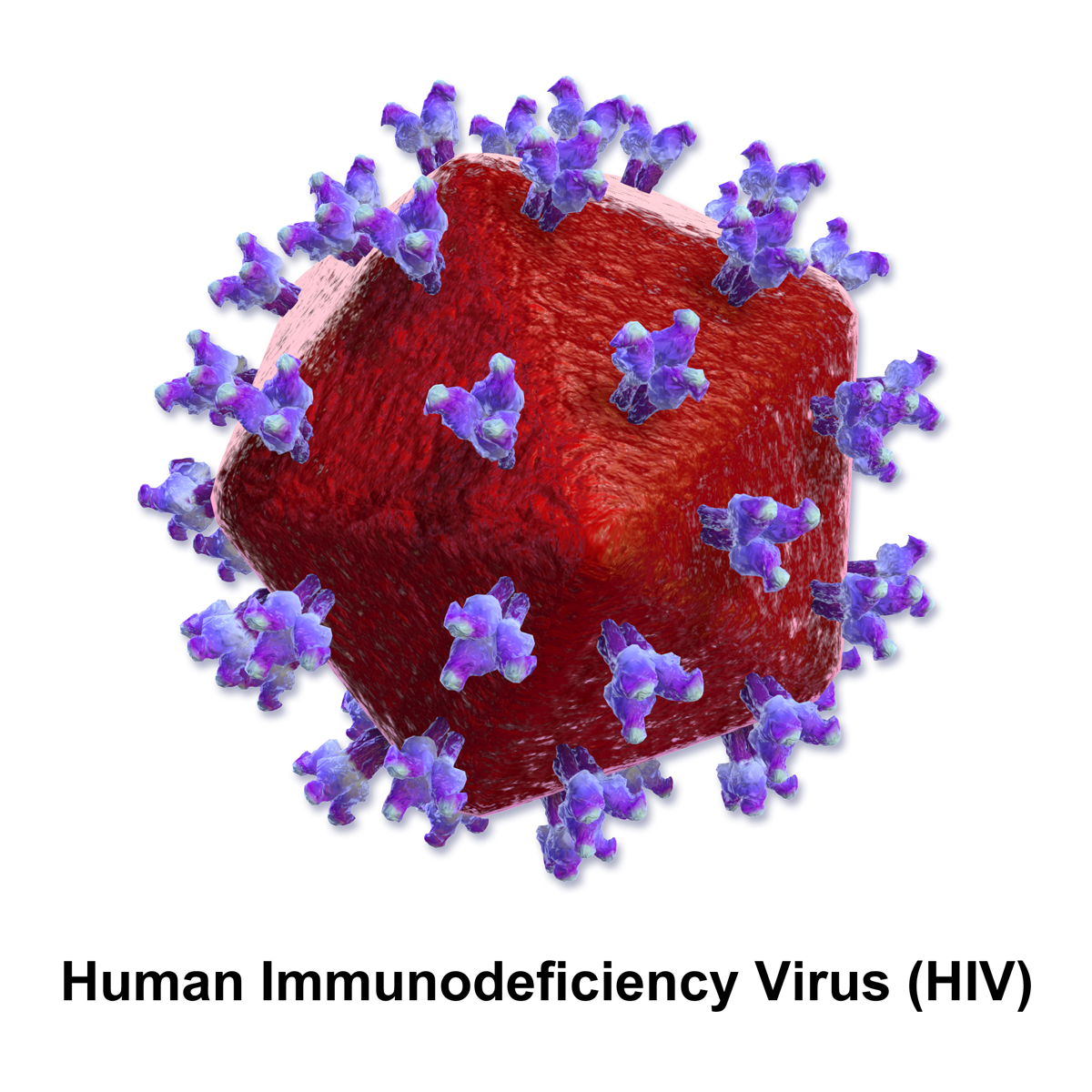

The protein-sugar the researchers created breaks down HIV’s sugar shield defense and stimulates an immune response, which could help in a creation of a vaccine for the virus. The virus surface is covered by a dense sugar shield produced by the host cell, said Hui Cai, who worked on this research for about two years as a postdoctorate at this university. The HIV shield stimulates a low immune response, meaning an individual’s body won’t try to create antibodies to fight against the HIV virus.

The low immune response is one reason there is no HIV vaccine available now, Cai added. HIV’s shield is similar to sugars found in the body, so immune responses to it aren’t as strong. The virus also has various strains and mutations, making it difficult to create a vaccine that could target HIV as a whole, Cai said.

Arvin Massoudi, a senior cell biology and genetics major, said he was impressed with the research.

[Read more: Companies can create custom DNA fragments. UMD researchers want to make sure they’re safe.]

“It’s a promising development in the fight to beat HIV,” Massoudi said. “Hopefully the treatment will be further refined and eventually reach human trials.”

In a two-month animal trial involving injecting the protein-sugar into rabbits, the molecule — designed using an HIV protein fragment — was successful in creating antibody responses against the HIV sugar shield in four strains of the virus. More than 60 strains of HIV exist.

The researchers’ long-term goal is to develop an actual vaccine, said Lai-Xi Wang, a biochemistry and chemistry professor at this university and a researcher on the project.

“Previously, people were not able to target the virus sugar, but now they will be able to, which is a first step,” Wang said. “The next step is to use this design to test known human-like primates like monkeys in combination with other vaccine candidates. Then we will be able to develop a truly effective vaccine.”

[Read more: UMD researchers find genes that may lead to flesh-eating bacterial infection treatment]

The researchers do not know when they will begin this phase of testing.

This research took about two years to complete, Wang said, but is part of a larger project that has gone on for more than 10 years. Previous work for the project included mimicking the sugar structure on the virus surface. This mimicry was necessary to create the protein-sugar that could break the HIV shield down.

Rockefeller University, the California Institute of Technology and the NIH, which supplies $400,000 per year for the project, are among the other institutions that have worked on the project.

Wang was excited with the findings and hopes to expand on this research in the future.

“As a scientist, you are always excited when you find something new and this is no exception,” Wang said. “It requires a lot of hard work to have that occasional big discovery and we want to continue to work on this subject and hopefully find more from the research we do.”